“Divers”ifying My

Curriculum

Exploring Diversity Assumptions, Bringing Awareness,

Breaking down Barriers, and Empowering Change

in Art History Instruction

Exploring Diversity Assumptions, Bringing Awareness,

Breaking down Barriers, and Empowering Change

in Art History Instruction

“The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe.

We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between

things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving,

continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is

present to us as we are.”

– John Berger, Ways of Seeing (1973)

Bringing diversity awareness into

my virtual classroom requires an acknowledgement and understanding of these

statements by John Berger. The act of seeing (which precedes spoken language)

“establishes our place in the surrounding world” and it is this visual acuity

that leads to further exploration of that world, encourages us to ask questions

and explore the possibilities of what we are seeing on a deeper plane. Just as we can only see what we look

at, we can only begin to make sense of what we see through the lens of our own

experiences. Providing the appropriate platform and encouraging students to approach the art we study

and “see” it through this lens of personal experience, enables a dialogue to

ensue that reveals belief systems and “start[s] a process of questioning”

(Berger 1973, p 5) these accepted systems. Rather than creating a “unit” on

diversity to teach in my class, Exploration 6 is an assessment of the content of

my course for opportunities to bring diversity awareness into the discussion

and examination of methods by which to establish interactions that promote the fleshing out of

the belief systems students bring to their interpretative viewing

experiences.

Survey of Art I & II are

courses that emphasize a Western and Eurocentric perspective of art

history. The images selected for the course were created within that perspective

and while the art of the course exhibits influence from cultures all around the

globe (i.e. Matisse and Picasso shared a fascination for African tribal art,

just as Whistler was enamored with the Orient), the predominant lens through

which the art is interpreted is Western. The selection of paintings offers a

“comprehensive” overview of the history of art. However, within this overview,

several groups are under represented based on gender, race, sexual orientation,

and ability. Often those who do appear in the text are omitted in the actual

teaching of the course due to time and “importance.” Of the images, I have

selected for consideration in this exploration many were not included in the

course content although they appear in the required text. I have selected images that are created

by and “representative” of different genders, sexual orientations, race,

ethnicity, ability, socioeconomic status, and bodies.

The primary objectives in these

courses assert that upon completion students will be able to

•

Identify significant artworks, their artists,

locations and the historical periods to which they belong.

•

Define important terms related to art and art

history.

•

Analyze works of art stylistically and relate

them to the society in which they developed.

•

Recognize stylistic changes in art by comparing

and contrasting artworks from different historical periods.

The current means by which

students are to accomplish these objectives include listening to lectures on

the subjects, reading the text, participating in discussion boards that expand

and challenge a student’s thinking on the subject, writing comparative essays

and taking assessments of the material.

Many of my students never really

look at the art we are studying. They simply interact with it in terms of

title, artist, medium, period, and significance. The more interesting or

seductive the piece, the more likely they are to remember or engage with it.

However, this way of looking and seeing is temporary and offers little

incentive to engage with other pieces of art outside of this course. This

practice also denies them the opportunity to evaluate themselves and their own

ways of thinking in their viewing experience. Berger asks the questions: “to whom does the meaning of the

art of the past properly belong? To those who can apply it to their own lives,

or to a cultural hierarchy of relic specialists?” (Berger, 32). Berger is referring to how the (mass)

reproduction of images and their availability to people operating outside of

the “art world” influences how meaning is formed around a piece of art. Taking

a closer look at the “meanings” that are derived from looking is the center of

this exploration.

In their work on engaging visual

culture, Karen Keifer-Boyd and Jane Maitland-Gholson discuss images as “cultural

meaning systems” (Keifer-Boyd and Gholson 2007, xvii). Their research reveals three critical

observations of these systems:

·

Meanings derived from images are built on both

past and current interpretations of images.

·

Meanings absorbed from images are part of the

present, since they refer to what we know at this moment.

·

Meanings we make from visual information are

foundational to future understandings. (Keifer-Boyd & Gholson 2007, xvii)

Although works of art (or visual culture) can articulate

time, place, space, culture, and intent to the viewer, they are mute objects

that require interpretation from the viewer. However, a viewer lacking

knowledge of the piece, its history or the culture within which it was created

can only draw from her own knowledge to draw meaning within the piece. As

students explore art, utilizing both their personal experiences and the inherent

information offered by a piece, they begin to discover

the cultural, social, political, and personal context within which their meanings

are shaped. The responses generated from this looking process illustrate how

“meanings of objects are derived from a continuum of memories” (Boyd, Amburgy,

& Knight 2007, p. 20) and support the idea that “memory is never objective

and fixed; rather it is subjective and fluid” (Boyd, Amburgy, & Knight

2007, p. 20).

“The significance of visual culture for art education rests not so much

in the object or image but in the processes or practices used to investigate

how images are situated in social contexts of power and privilege.”

(Keifer-Boyd &

Gholson 2007, xviii)

In order to begin a dialogue that

illuminates these preconceived ideas and “assumed truths,” I will engage

students in cooperative conversations about each of the selected pieces prior

to discussing the work or works “in class.” Although the discussions will take

place (ideally) before the image in introduced within the course context this

is not necessary. Students will be encouraged toward personal interpretation

outside of a factual or popular interpretive/historical narrative. Through the act of questioning and

listening, I will look for assumptions about gender, race, ability, sexual

orientation, etc. and will revisit the discussions to decode language and look for

missed readings of the work to inform further discussion. The initial questions

are derived from the VTS (Visual Thinking Strategies) approach to viewing art.

These questions include simple open-ended questions such as: “What is going on

in this piece?” “What do you see that makes you say that?” “What else do you see?”

While these probes seem simple, they are meant to allow the discussion to flow

from the viewer’s own viewing style rather than a traditional art historical

perspective. Students are exploring and filling in the gaps themselves, rather

than looking to the instructor for meaning. Follow up questions will follow the

lead of those participating in the discussion and attempt to decode the

assumptions behind the responses from the students. Some of these may include:

“Imagine this was a [white, black, homosexual, disabled, able bodied,] [man,

woman, transgender]. How (do you think you) would respond to this piece? What

(do you think) makes you say that?”

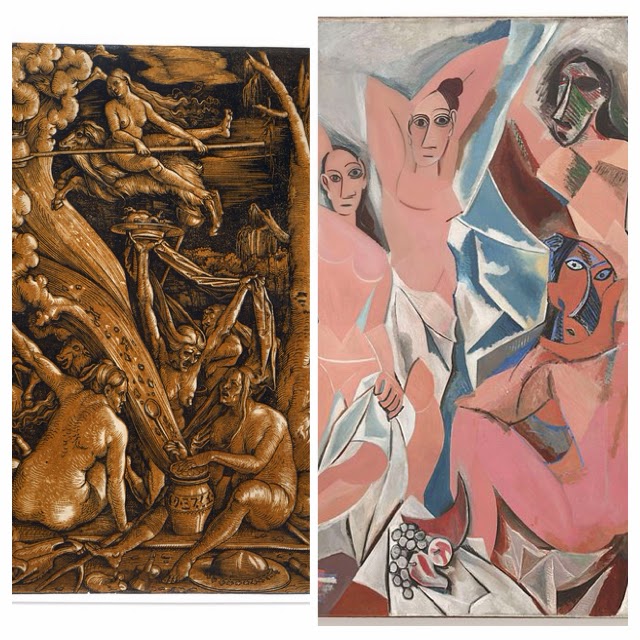

Below are a few of the selected images that will be used to explore difference and start the conversation of diversity. “Difference” exists in many forms: gender, race, age, intellect, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religion, physical appearance, character traits, professions, cultures, and personal preferences. Each of these differences denotes a way in which we are like or not like another person. People use these differences to assess themselves and others, as well as determine what is valuable and desirable and what is not. Unfortunately, these ideas of difference are cultural constructions rather than natural progressions of the process of the examination of self and other (Jhally 2009). As in most cultures attempting to assign categories for understanding various groups within and without, these constructions assign an image of “normal” that both alienates and deprives those who do not fit within these categories.

|

| Venus de Milo (Aphrodite of Milos) & Alison Lapper (Pregnant), by Marc Quinn |

|

| George Washington, by Jean-Antoine Houdon & Jean-Baptiste Belley by Girodet-Trioson |

|

| Satan Devouring one of his children, Francisco de Goya & Ophelia, Millais Two Fridas, Frida Kahlo & Insane Woman, Gericault |

|

| Branded, Jenny Saville & Nude Self-Portrait, Egon Schiele Self-Portrait, Robert Mapplethorpe & Self-Portrait, Modersohn-Becker |

|

| Witches Sabbath, Hans Baldung Grien & Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Picasso |

“Before a society can change its behaviors, beliefs must evolve through a self-reflective process. Looking at and articulating beliefs about the visual images that surround them can help students to develop explicit processes for thinking through beliefs and the behaviors that rise from those beliefs” (Keifer-Boyd & Gholson 2007, xviii).

"There is no such things as the innocent eye. We are not always seeing as clearly as we think we are. The brain distorts the reflection and if it's distorting the reflection of ourselves, what is it doing in terms of your reflections or patterns of other people?"

- Helen Turnbull, Inclusion, Exclusion, Illusion and Collusion, 2013

Resources:

Berger, J. (1973). Ways of seeing. London: British Broadcasting.

Burnham, R., & Kee, E. (2011). Teaching in the art museum: Interpretation as experience. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York: Minton, Balch & Company.

Keifer-Boyd, K., Amburgy, P., & Knight, W. (2007). Unpacking Privilege: Memory, Culture, Gender, Race, and Power in Visual Culture. Art Education, 60(3), 19-24

Keifer-Boyd, K., Amburgy, P., & Knight, W. (2007). Unpacking Privilege: Memory, Culture, Gender, Race, and Power in Visual Culture. Art Education, 60(3), 19-24

Keifer-Boyd, K., & Gholson, J. (2007). Engaging visual culture. Worchester, Mass.: Davis Publications.

Perkins, D. (1994). The intelligent eye: Learning to think by looking at art. Santa Monica, CA: Getty Center for Education in the Arts.

Rice, D., & Yenawine, P. (n.d.). A Conversation On Object-Centered Learning In Art Museums. Curator: The Museum Journal, 289-301.

Dr. Marylin Sanders Mobley, The Paradox of Diversity, 2013

Dr. Marylin Sanders Mobley, The Paradox of Diversity, 2013

Helen Turnbull, Inclusion, Exclusion, Illusion and Collusion, 2013

The Codes of Gender: Identity and Performance in Pop Culture 2009, 73 min. http://pennstate.kanopystreaming.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/node/41623

List of Works Selected from the course selected to

Explore Diversity Assumptions, Bring Awareness, Breakdown Barriers, and Empower Change:

Introduction//Module 1:

Venus de Milo

Alison Lapper, Pregnant, Mike Quinn

Module 2: Art of the Northern Renaissance

Arnolfini

Portrait, Jan van Eyck

Deposition, Rogier van der Weyden

Virgin and Child,

Jean Fouquet

Module 3: Art of the Early Renaissance (Italy)

Donatello, David

Boticelli, Birth of

Venus

Module 4: Art of the High Renaissance and Mannerism

Michelangelo, David

*Bologna, Abduction

of the Sabine Women

Module 5: Art of 16th Century Northern Europe and

Spain

*Hans Baldung Grien, Witches

Sabbath

*Levina Teerlinc, Elizabeth

I as a Princess

Module 6: Art of the Southern Baroque

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Hologernes

Diego Valazquez, Las

Mininas

Module 7: Art of the Northern Baroque

Judith Lester, Self-Portrait

*Louis Le Nain, Family

of Country People

Module 8: Art of the Rococo and Neoclassicism

Jean Honore Fragonard, The Swing

*Adelaide Labille-Guiard, Self-Portrait with Two Pupils

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George

Washington

*Horatio Greenough, George Washington

Module 9: Art of the 19th Century I

*Girodet-Trioson, Jean-Baptiste

Belley

Ingres, Grande

Odalisque

Gericault, Insane

Woman

Goya, The Third of

May & Satan Devouring One of His

Children

Courbet, The Stone Breakers

Eakins, The Gross Clinic

*Henry Ossawa Tanner, The

Thankful Poor

John Everett Millais, Ophelia

Module 10: Art of the 19th Century II

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergere

Mary Cassatt, The

Bath

Gaughin, Where do

we come from? What are we? Where are We Going?

Rousseau, Sleeping

Gypsy

Munch, The Scream

Rodin, Walking Man

Module 11: Art of the Early 20th Century

Derain, The Dance

Nolde, Saint Mary

of Egypt Among Sinners

*Egon Schiele, Nude

Self-Portrait

*Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait

Picasso, Les

Demoiselles d’Avignon

*Frida Kahlo, The

Two Fridas

Module 12: Art Since 1945

Willem de Kooning, Woman I

Roy

Lichtenstein, Hopeless

Audrey Flack, Marilyn

Duane Hansen, Supermarket

Shopper

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #35

Lorna Simpson, Stereotypes

*Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait

*Jenny Saville, Branded

*Leon Golub, Mercenaries IV